Infectious disease and cattle health: how much data is enough?

Case study developed in collaboration with Christl Donnelly, deputy chair and statistician on the Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB, member of RSS Statistics Under Pressure Steering Group, RSS Vice President for External Affairs, Professor of Applied Statistics at University of Oxford and Visiting Professor at Imperial College London.

Summary

In the 1990s, the number of British cattle herds becoming infected with the bacterium that causes bovine tuberculosis (TB), Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis), was increasing. This severely impacted farming businesses because infected cattle had to be slaughtered to prevent further spread. Badger culling had been undertaken in some areas to limit the transmission of M. bovis from badgers to cattle, but there was limited evidence about how effective culling was.

In 1998 the government established an independent scientific group to investigate the effectiveness of two types of badger culling. Unexpectedly, an interim result of their study suggested that one type of culling had a detrimental impact on TB incidence, increasing the number of cattle herds infected.

Should the trial continue to collect further data and be more certain of the results? Or should this culling approach be stopped, to avoid both the heightened risk of infection in cattle (with associated slaughter of affected cattle) and counterproductive badger culling? This case study explores how statistical evidence intersects with other policy, economic, ecological and ethical considerations to inform policy-making.

What was the problem?

Bovine TB (caused by

M. bovis) is an infectious disease similar to human TB, which is caused by

M. tuberculosis. The incidence of bovine TB in British cattle herds was increasing in the 1990s. Infected cattle must be slaughtered to prevent the spread of

M. bovis to other cattle and to humans who either consume unpasteurised dairy products or come into close contact with cattle. The slaughtering of cattle for disease control is expensive for taxpayers and for the dairy and beef farming industries, putting at risk the economic sustainability of agriculture in the UK.

M. bovis is transmitted within cattle herds, but also between other animals including deer and badgers. From the 1970s to mid-1990s,

over 20,000 badgers were culled in England as part of policies to control cattle TB. Badgers are a protected species in the UK and badger culling is a contentious topic. The culling policies were strongly opposed by many conservation stakeholders, while many farming stakeholders advocated for more badger culling to better control the disease in cattle.

There was limited data on the effectiveness of badger culling for reducing the incidence of TB in cattle. The government (the Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food [MAFF], now part of the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs [Defra]) therefore wanted better evidence to inform their policy on badger culling. They wanted to measure the effectiveness of two approaches to badger culling on bovine TB – smaller-scale local culling in response to outbreaks (reactive localised culling) and larger-scale yearly widespread culling (proactive annual widespread culling) – compared to no culling.

What was done?

"The ISG had a lot of work to do even at the design stage. We had to overcome opposition to randomisation from some officials who thought that they could predict which areas would attract less interference from anti-culling activists with trapping than others. Everyone wanted a robust trial, but to some randomisation seemed perverse."

The government established a committee of scientific experts (the Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB, ISG) including statisticians Professors Christl Donnelly and past RSS President Sir David Cox. The ISG was to design, oversee, analyse, and interpret a large, randomised trial from 1998 to 2005. Thirty areas across England were randomly assigned to no culling, reactive localised culling, or proactive annual culling.

The trial was planned with interim analyses. These were to be conducted by the statisticians in the ISG, and the results would be kept confidential unless a significant effect was found – in which case other ISG members and government ministers were to be alerted. An independent statistical auditor evaluated the study design, the analysis plan and the results obtained.

In the autumn of 2003, an interim analysis showed that reactive localised culling had an estimated detrimental effect on the incidence of bovine TB. There was a 27% increase in TB following reactive localised culling compared to no-culling areas. This finding was surprising as only reductions in cattle TB had previously been thought to be linked to culling. The finding was debated and stress-tested within the ISG and in discussion with government officials. Several officials were seriously concerned that the findings were not plausible.

"We checked, double-checked and then checked again, rewriting the code independently to ensure that no error had caused the result. Every time reactive badger culling was associated with more TB in cattle."

The ISG had to decide whether to advise government to stop the reactive localised culling arm of the trial or to continue collecting data. Following an intense period of group discussions, the ISG recommended six more months of data collection (of which only six weeks would have involved further badger culling, as trapping was suspended each spring to avoid separating mothers from dependent cubs) to obtain further information on TB incidence and enable further analysis and increased confidence in the result obtained – though they stated that it was unlikely that the result would change significantly with only six months’ additional data.

"There was the pressure of having to make a recommendation and there was also time pressure – we didn’t want more reactive culling to start until a decision had been made."

In addition to roundtable discussions between the ISG and government officials, the ISG chair and deputy chair (statistician Professor Christl Donnelly) spoke directly to ministers to ensure that they understood the results and the associated uncertainties in the estimates due to the design of the study and the duration of data collection. Ministers, having sought advice from many sources and considered the scientific, policy, legal and ethical perspectives, ultimately decided to discontinue reactive culling within the trial, a decision the ISG supported.

What factors were balanced?

The trial originally planned to collect data from each area for five years on average, but only just over half of the planned data on reactive culling had been collected when the interim analysis detected a significantly detrimental effect. The ISG had to decide whether to advise that the reactive culling arm of the trial continued or be stopped. From a purely scientific or statistical perspective, with no other considerations, it would have been better to continue with reactive culling to allow more comparative data to be collected and be more certain of the findings.

"In statistics we are used to estimates and confidence intervals, but the government had to make a binary decision – to continue with reactive culling in the trial or not. There were risks on both sides. There was no pretending that the way forward was obvious."

However, this option risked increasing the transmission of M. bovis, which could have led to more cattle being slaughtered. It also would have involved the culling of badgers despite evidence that this culling was increasing rather than decreasing transmission – badgers are protected under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992 and are not to be taken, injured or culled without legal justification. Further reactive culling would have also incurred additional costs – both financial (government funding) and in terms of resource – as badger culling required substantial efforts from a large team of government staff to set many traps over many nights over several years. Finally, farmers may have considered the government liable for their losses where bovine TB was detected in trial areas subjected to further reactive culling.

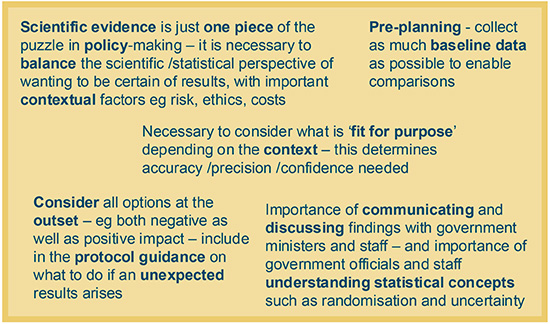

Infographic illustrating factors that had to be balanced.

What was the impact of these decisions?

Discontinuing the reactive arm of the trial meant minimising the risk of counterproductively culling badgers, spreading bovine TB, and slaughtering additional cattle, as well as minimising the costs.

"The apparent loss of localised reactive culling as a potential policy polarised everything. It became clear from the final results of the trial that if culling were to be effective, it needed to be larger-scale and repeated."

The reactive culling arm of the trial was similar to earlier badger culling approaches in England in terms of scale and in responding after M. bovis was detected in cattle. This trial was therefore important in testing the impacts of badger culling at both widespread and localised scales. The trial also yielded insights into badger behaviour and mechanisms of M. bovis transmission that have informed subsequent infectious disease control strategies.

Although the reactive-culling arm of the trial was suspended, the proactive-culling and no-culling arms of the trial continued, meaning that the effectiveness of proactive culling could still be assessed. The trial found that proactive culling did reduce bovine TB incidence significantly, but the reductions were limited (23%) and could take years to be seen. Furthermore, proactive culling also led to increases in TB incidence among herds in surrounding areas. This is another example of how different aspects of scientific evidence, along with their corresponding costs and ethical considerations, must be balanced to inform policy-making.

What are the key learnings?

This case study exemplifies how scientific evidence is just one piece of the puzzle in policy decision-making and cannot be considered in isolation. The context, including ethical considerations and costs, must also be taken into account. The role of the statisticians in this example was to be honest brokers of the evidence rather than advocating for a specific outcome – focussing on ensuring that the results and their limitations were understood.

This example also highlights the need to consider what sort of finding is sufficient and ‘fit for purpose’ depending on what it is needed for. In this instance, it was not necessary for the estimate of the effect of reactive badger culling on cattle TB to be based on as many years of data as originally planned. An earlier indication that reactive culling was not advantageous and appeared to increase risks to cattle herds was sufficient to inform decision-making, meaning that further spending and the risk of additional harm could be avoided.

With hindsight, the ISG members should have pushed officials to flesh out strategies for all possible outcomes at the outset of the trial – including the possibility of culling being minimally beneficial or even detrimental (the reasonable worst case scenario).

It also would have been helpful to monitor badger ranging behaviour from the outset. This data would have allowed the ISG to investigate the mechanism by which reactive badger culling led to increased risk to cattle.

Infographic illustrating key learnings.

Resources

- Bovine TB: The Scientific Evidence (Final Report of the Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB), 2007

- Badger culling in England: The Randomised Badger Culling Trial (RBCT) - fact sheet

- An Epidemiological Investigation into Bovine Tuberculosis PB4870 (Second Annual Report of the Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB), 1999

- Impact of localized badger culling on tuberculosis incidence in British cattle, Donnelly and others, Nature, 2003

- Positive and negative effects of widespread badger culling on tuberculosis in cattle, Donnelly and others, Nature, 2006

- Effects of culling on badger Meles meles spatial organization: implications for the control of bovine tuberculosis, Woodroffe and others, Journal of Applied Ecology, 2005