Understanding poverty depends on more than good intentions; it depends on good data. Yet, in certain cases, the data used to measure and understand poverty, and the routes to accessing that data, fall short.

In partnership with the Centre for Public Data, today we published an interim report that takes a close look at the gaps in the data underpinning how poverty is understood in the UK, and the consequences of those gaps for policymaking, research and civil society.

You can read the full interim report here.

Listening to those closest to the problem

The report is grounded in qualitative research, drawing on interviews and roundtable discussions with more than 60 stakeholders across government, academia and civil society. Many of these participants work to improve the lives of people experiencing poverty or rely on data every day to influence policy and practice.

Their message was clear: while the UK has a wealth of economic and social data, key aspects of poverty remain poorly captured, or entirely invisible.

Who is missing from the data?

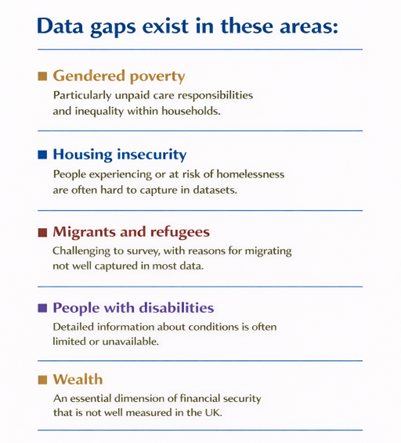

The research identifies several areas where existing data does not adequately tell us about people’s experiences of poverty.

When these experiences are missing or under-represented, it becomes far harder to answer fundamental questions such as who is most at risk, how poverty changes over time and which interventions actually make a difference.

Barriers to using the data we already have

The report also highlights persistent challenges in accessing and sharing administrative data, even where it exists.

In particular, improved access to the highest quality data held by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) could significantly enhance poverty research. However, stakeholders described a system characterised by:

- Case-by-case approval processes for the best data, contributing to long application timelines

- Risk-averse approaches to data sharing, encouraged by the legislative framework, that lead to tight access protocols

- Technical and infrastructure constraints that make data less accessible to some

Civil society organisations – especially those without academic partners – face some of the steepest barriers, as timelines for project approval are often too long to be practical for their purposes. Their challenges often receive less attention than they deserve, despite the crucial role such organisations play in understanding and responding to poverty on the ground.

Why this matters

Data gaps are not just a technical issue. They shape what problems are visible, whose experiences are taken seriously and which policy solutions are considered possible.

Without these foundations, evidence-informed decision-making is undermined and opportunities to reduce poverty are missed.

What happens next?

We will be using this interim report as a stepping stone to deeper engagement.

The Society will use the findings to support further conversations across government, the research community and civil society. As part of this work, we will be hosting two in-person workshops focused on:

- Addressing barriers to data access, especially for non-academic users (February 5)

- Improving disability data for practical, public interest research (February 19)

By bringing together practitioners, data producers and users, we aim to move from identifying gaps to developing practical solutions.

Building a fuller picture of poverty

Better data alone will not end poverty. But without it, the effectiveness of poverty alleviation efforts is limited.

This report is a step towards a statistical system that tells a more complete story about poverty and living standards in the UK and better equips those working to improve them. We look forward to continuing this work with partners across the system.

You can read the full interim report here.

To enquire about attending our workshops or to otherwise contribute to our research, please contact Dakota Langhals, RSS Policy Researcher, at d.langhals@rss.org.uk or policy@rss.org.uk.

Thank you to the Insight Infrastructure programme for their support. Developed by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), it aims to democratise access to high-quality quantitative and qualitative data and evidence through open collaboration and innovation, working towards a more equitable and just future, free from poverty.